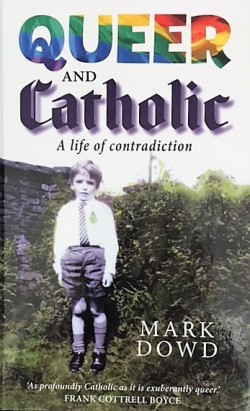

Last week I wrote about a book which resonated. I thought I might feel more detached about Mark Dowd’s just published memoir Queer and Catholic – I’m neither gay nor Roman Catholic. Nonetheless our common humanity made it both pleasurable and instructive. We do have our age in common – he’s a year younger than I am. It was at university that I was first aware of so many fanciable young men coming out. The same year Dowd was nipping between stints on the adjacent Gay Soc and Catholic Society stalls at the Exeter Freshers’ Fair, I was consoling female friends in the Sussex Union bar when our fellow student Simon Fanshawe didn’t respond to their flirting. Also I did, briefly, go to a Catholic school, where as Dowd found there was relatively little bullying and much gentleness, though he was taught by Brothers rather than by Daisy (Sister Des Anges), Ratty (Sister Mary Raphael) and Revvie (Reverend Mother).

Dowd grew up the son of northern working class parents, a decade or so after Alan Bennett and David Hockney, contemporaneously with Jeanette Winterson. He began training as a priest but switched to academia and then journalism, a practising but critical Roman Catholic through steady and not so steady relationships, the 1980s AIDS epidemic, the homophobia of Cardinal Ratzinger, and the revelations of paedophilia in the church (he only came across one instance of this and is otherwise complimentary about the priests who taught him). His tone starts rueful and witty: he knew he was gay, or at least “different” from early childhood: “A Catholic blessed (or cursed) with same sex attraction is rather akin to the orthodox Jew who cannot get the smell of sizzling bacon rashers out of his head, or a fervent Muslim with an irresistible devotion to single malt whisky.” (p.8). See what I mean about common humanity? This is a kind book: to paraphrase Jo Cox, there is more in it to unite us than divide us. So we read his story of adolescent encounters, of fearing discovery, of naivety and disappointment and lust and adoration with, I hope, equal empathy whatever our faith and orientation.

A theme throughout is the illogicality of the Catholic church not accepting same sex attraction, when so many of its practitioners are gay and so many of its practices are so attractive to gay men. At his interview for training to be a priest, Dowd is asked if there is anything the college should know about him. In trepidation, he stammers he is gay. “‘Put it this way,’ said Father Weston. ‘I don’t think you’ll be the only one.'”(p. 71)

It’s very funny in parts: the much older partner who pretends for the sake of appearances to be his father and the consequent difficulties of explaining two dads; the intellectual Oxford Dominican friars who make peach wine in the bathtub; the Vatican priest who greets him with friendship in St Peter’s Square before realising he knows Dowd’s face from a BBC documentary about queer Catholics. It’s very touching: his parents never specifically accept his gayness but they give him brightly coloured nylon double sheets as a housewarming present when he moves in with his partner. Sometimes it’s touching and funny: at the funeral of an AIDS victim friend, the Mother Superior eulogises that his key attributes were “infectious” and none of the mostly gay congregation know where to look.

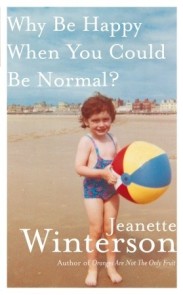

Dowd alludes with a light touch to the loneliness of longing for both sex and love, against the Church’s requirement of celibacy (for a compassionate and balanced fictional treatment of this, see John Boyne’s A History of Loneliness). His writing is increasingly emotional as the book goes on: where Winterson describes in Why be happy when you could be normal? the (entirely justifiable) anger she has to resolve, Dowd learns to cry and then what his crying teaches him about himself and others. Anyone who’s read the recent Robert Webb memoir How Not To Be a Boy, or heard Grayson Perry talking about identity will appreciate this openness: Dowd bares his feelings and thoughts to the world with a candidness that is even now unusual. He’s narrated the audiobook himself and my guess is it would be an emotional listen. Think David Sedaris, but with a lot more shared insight. And for the memories of parents and home, think Alan Bennett, or Hockney’s wonderful pictures of his mother. They are all related, and related to us all.

The book is political with a small “p”: he discusses others’ research into homosexuality in the Church and poses the question himself: “How can you use the antiquated language of ‘disorder’ about a perfectly naturally occurring minority phenomenon…when you rely on such people to represent Jesus in the daily acts of administering the sacrament?” (p.143). In his BBC career he fronts documentaries about Rwanda and Sarajevo; he discusses male mental health and goes to El Salvador to help set up a radio station in a remote and poverty stricken area. But there is always a light touch, a joke, an anecdote, to help us through the darkest moments.

It’s one to be read in conjunction with others: try Winterson’s Oranges are not the Only Fruit which jollies along in the caricature which was all the young Winterson could bear to reveal of her childhood, and the much darker Why Be Happy when You Could Be Normal? which tells us what really happened. The title is a quote from her fearsome adoptive mother. Read it in conjunction with what Alan Bennett does NOT say; read it in conjunction with the fiction of John Boyne and Elena Ferrante. Read these books whether you are gay or straight or trans or whatever; whether you have faith or none; whether you are old or young or left or right wing or “apolitical”.

It’s one to be read in conjunction with others: try Winterson’s Oranges are not the Only Fruit which jollies along in the caricature which was all the young Winterson could bear to reveal of her childhood, and the much darker Why Be Happy when You Could Be Normal? which tells us what really happened. The title is a quote from her fearsome adoptive mother. Read it in conjunction with what Alan Bennett does NOT say; read it in conjunction with the fiction of John Boyne and Elena Ferrante. Read these books whether you are gay or straight or trans or whatever; whether you have faith or none; whether you are old or young or left or right wing or “apolitical”.

“…to this day the brass crucifix that my parents had given me, a holy communion present when I was seven…remains unstable and slightly skew-whiff on account of a botched repair job with the superglue.” (This after using it as a missile during a row). “So when I see the good Lord staring at me at an odd angle, I think of torrid times with Pablo and the brokenness of fallen humanity.” (p175)

I think that means there’s hope for us all.

©Jessica Norrie 2017

Jessica you always come up with something beautifully written about something fascinating. I adore reading you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Aw… sometimes I wonder whether the time I put into the blog is worth it and then you come up with a comment like that! Thank you so very much.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Credit where credit’s due Jessica! Px

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Jessica. That’s a very perceptive and faithful review of the book. I hope your readers will think it a good investment.

It was fun and occasionally painful to write.. Bitter sweet.!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fun but brave I think, and I’m

not surprised it was painful Anyway I shall look forward to volume 2, after you’ve had a break.

LikeLike

What a wonderful review – this one is going on my tbr list.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Mary – I’m sure you’ll enjoy it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on Smorgasbord – Variety is the spice of life and commented:

It is Friday and one of my weekly visits to Jessica Norrie’s blog and this week she reviews the book Queer and Catholic by Mark Dowd.. Jessica shares her thoughts on the book which are definitely worth reading as is the book judging by her review. Please head over and read this thought provoking and entertaining review. I loved it…including “Sometimes it’s touching and funny: at the funeral of an AIDS victim friend, the Mother Superior eulogises that his key attributes were “infectious” and none of the mostly gay congregation know where to look.” #recommended

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Sally. Yes, and there are many more moments like this so I hope you enjoy them!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Beautifully written review of a book I would never have heard of but for your blog.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Neville. I give the link in the post for anyone who wants to buy early for Christmas!

LikeLike