How hard can it be to find the main character (MC) in a novel? No prizes for David Copperfield, Jane Eyre, Mrs Dalloway. Playwrights may play tricks: Julius Caesar dies in Act 1, we’re left Waiting for Godot who may not even exist, and Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are dead. But novels are easy.

Or are they? Even the classics can fool us. Are the four Little Women equally important? As an avid bookworm and would-be writer I should have identified with Jo, but the recent very good film confirmed what I’d suspected since childhood. Amy leads the pack.

Some successful modern novels deliberately make it hard to identify the MC. The reader can be tricked even when the name’s in the title. Madeline Miller’s beautiful The Song of Achilles (2011) is, you would think, the story of Achilles. But it’s told by his  life companion Patroclus. From inside Patroclus’ head, we experience his compelling conflicts and joys, although Achilles’ story is the more glorious and dramatic. So which is the main character? (Digression: Miller makes them so lifelike she dispels the myth that classical history is for Eton posh boys. Do try this unputdownable yarn featuring palaces, caves, love, death, war, the sea, women both unfortunate and powerful, interference from the gods and some daring plot changes.)

life companion Patroclus. From inside Patroclus’ head, we experience his compelling conflicts and joys, although Achilles’ story is the more glorious and dramatic. So which is the main character? (Digression: Miller makes them so lifelike she dispels the myth that classical history is for Eton posh boys. Do try this unputdownable yarn featuring palaces, caves, love, death, war, the sea, women both unfortunate and powerful, interference from the gods and some daring plot changes.)

Hamnet (Maggie O’Farrell, 2019) was Shakespeare’s son, one of three children. The novel begins from Hamnet’s point of view but for a unarguable reason it doesn’t continue that way. From about a third in it’s more about his relations and his part in their lives. Hamnet’s mother’s point of view takes up the most space, among others. So is she the main character? Or is the MC still the eponymous hero, or even William Shakespeare because without him we wouldn’t know this family existed or have so much detail of their daily lives?

Hamnet (Maggie O’Farrell, 2019) was Shakespeare’s son, one of three children. The novel begins from Hamnet’s point of view but for a unarguable reason it doesn’t continue that way. From about a third in it’s more about his relations and his part in their lives. Hamnet’s mother’s point of view takes up the most space, among others. So is she the main character? Or is the MC still the eponymous hero, or even William Shakespeare because without him we wouldn’t know this family existed or have so much detail of their daily lives?

Monica Ali’s Untold Story (2007) poses a similar question. As it opens, three friends are at a birthday tea in Middle America. The narrative presents them as all apparently of equal status. The fourth guest, Lydia, doesn’t turn up. When we do meet her later, it turns out she’s crucial. But she’s not the childless suburban divorcee they think they’ve made friends with. She was born a UK aristocrat who had an unhappy marriage with the heir to the throne. Later, she escaped paparazzi hounding to live under the radar in this backwater. Princess Diana is never mentioned by name, but she looms on every page, through references to recognisable incidents, characters and dresses from “Lydia’s” former life. The reader doesn’t need telling who the character is based on; there would be no Untold Story without Diana. So who is the main character (and who’s that on this cover?) Remember, outside fiction “MC” stands for Master of Ceremonies.

Monica Ali’s Untold Story (2007) poses a similar question. As it opens, three friends are at a birthday tea in Middle America. The narrative presents them as all apparently of equal status. The fourth guest, Lydia, doesn’t turn up. When we do meet her later, it turns out she’s crucial. But she’s not the childless suburban divorcee they think they’ve made friends with. She was born a UK aristocrat who had an unhappy marriage with the heir to the throne. Later, she escaped paparazzi hounding to live under the radar in this backwater. Princess Diana is never mentioned by name, but she looms on every page, through references to recognisable incidents, characters and dresses from “Lydia’s” former life. The reader doesn’t need telling who the character is based on; there would be no Untold Story without Diana. So who is the main character (and who’s that on this cover?) Remember, outside fiction “MC” stands for Master of Ceremonies.

These three authors play highly skilled hide and seek with their MCs within the accessible literary fiction genre. Going downmarket (absolutely no disrespect) M W Craven’s 2018 detective novel The Puppet Show (2018) is an MC master class. Disillusioned detective Washington Poe appears on every page and we travel with him. We know only what Poe knows, experience all incidents alongside him. We see the world through Poe’s jaundiced eyes, share his bafflement on bad days and recover with him later. The conclusions we reach are Poe’s conclusions. So whether we like him or not, we empathize with him because he’s the most interesting and immediate character. Which is great news for Craven, since The Puppet Show is the first of a Washington Poe series. His map is the one to follow if those of us toiling on writing’s lower slopes are to avoid losing our MC at base camp.

These three authors play highly skilled hide and seek with their MCs within the accessible literary fiction genre. Going downmarket (absolutely no disrespect) M W Craven’s 2018 detective novel The Puppet Show (2018) is an MC master class. Disillusioned detective Washington Poe appears on every page and we travel with him. We know only what Poe knows, experience all incidents alongside him. We see the world through Poe’s jaundiced eyes, share his bafflement on bad days and recover with him later. The conclusions we reach are Poe’s conclusions. So whether we like him or not, we empathize with him because he’s the most interesting and immediate character. Which is great news for Craven, since The Puppet Show is the first of a Washington Poe series. His map is the one to follow if those of us toiling on writing’s lower slopes are to avoid losing our MC at base camp.

The idea for this post came from reading a friend’s ms. She tells me the main character is Anna, her narrator who’s preoccupied by a younger man, Zoltán. From inside Anna’s head, we learn about Zoltán mainly through what he tells her – and he’s reticent by nature. Even so, the reader has a much more vivid impression of Zoltán, because Anna’s character/events arc is vague while Zoltán’s story is dramatic and emotional. Anna is hiding within an otherwise clearly written story, and that simply ain’t right for a main character. (These aren’t their “real” names. I’m happy to do ms critiques but I’d never blog about recognisable details before they’re published.)

One confusion can cause so many others we have to abandon the game. Let’s not mince words: hiding the MC can also mean losing the plot (reader’s nightmare) or muddying the genre (writer’s, agent’s, publisher’s, marketing nightmare).

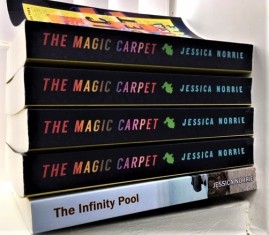

Anyway do as I say, not as I did. Writing with the blissful freedom of not having studied the rules, I thought my Infinity Pool was clear enough, but one review complained the MC vanishes and reappears. Then I couldn’t decide between The Magic Carpet‘s narrators so hung on to five of them (with clearly separated chapters for each voice.) My third novel, currently blocking publisher’s inboxes, does have one clear leading voice, but there was an early struggle between three characters and for months the least suitable muscled to the fore.

I’ve made a vow: Novel 4 will learn from Washington Poe. My MC will announce her/him/their self on page 1 and not leave your sight until The End. The next task is to make them interesting enough for you to stay that long. But that’s another story.

©Jessica Norrie 2020

Hamnet is such a layered novel that the MC is probably a combination of all three!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, I think whenever you write a novel that originates with a famous person that will happen. Thank you for commenting.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I had some developmental editorial advice on this exact thing in my new book, Jessica. I am busy rewriting parts of it to ensure the MC is clearly defined. WRT Little Women NO! No! I never really liked Amy and her marriage to Laurie ruined the book for me. This is why it isn’t a favourite for me. Jo is my MC.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think MCs pose a common difficulty even among well established writers and famous ones. Every book I pick up atm seems to have multiple equal POVs and flaunt them! I don’t mind either way as long as its well done, but am retreating in the direction of convention in the hope of getting published! As for LW, we’ll have to agree to disagree. Actually years since I read it and don’t feel all that strongly, but the film clarified why I’d never been as keen on Jo as I thought we were all supposed to be. Thanks for commenting. .

LikeLiked by 1 person

My pleasure, Jessica. I also listened to the advice I was given about the MC, hence the rewrite.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very interesting perspective in this post Jessica. Great topic, who is the main character? 🙂

LikeLike

One reason I did this is because an agent told me if he cant identify the MC he doesn’t take the book! Worth knowing! Thanks for reading.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Absolutely worth knowing. Much appreciated. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting timing for this post! I’ve just started a new novel, and I want to use multiple points of view and timelines (just to see if I can do it, more than anything else). Then last week as I’m working on it, I’m thinking, Wait a minute. Whose story is this supposed to be, anyway?

LikeLike

I think if you’ve only just started and you want to try out multiple POVs because you haven’t written that way before, you should go ahead. The main one will emerge for itself most likely, and you’ll find you make those sections longer and commit to them more. Much later in the process you can decide whether to stick with the multiple POVs or make it a single narrator after all. It’s such an interesting process I’d stick with it a bit longer, but it’s definitely best to keep each POV in a separate chapter or section. No wonder you say you’re flummoxed!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fascinating Jessica.. I must that recently I have read a couple of books that had me flummoxed until about half way into the story… great examples… especially Little Women and having seen the latest film I am with you on Amy.. I loved her speech about her prospects in life and her requirements for marriage…I have pressed for Sunday afternoon.. hugs

LikeLiked by 2 people

Flummoxed is such a good word! It happens to me more and more. But I was pleased the Little Women saw things my way. I was never in a muddle about that! Thanks very much for pressing, that will spread me through the week a bit. Hugs and bon weekend!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Enjoy yours too…and delighted to share..hugsx

LikeLiked by 1 person

Flummoxed is one of my favorite words as well. I’ve had occasion to use it rather more often lately than I would like.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh dear!

LikeLiked by 1 person