Well that’s annoying. I wanted to use italics in my title and WordPress won’t let me. Maybe if I upgrade to the paid version… meanwhile I’ll put quotes in this post, which I’d normally have italicised, in purple so the original italics still show up.

The word italics comes from Latin. The print style was named for the Venetian printer who used it first. The adoption of italic fonts has a fascinating history that leads the procrastinating blogger down many Googling byways. Do explore them one wet Sunday afternoon.

We use italics for emphasis. Just as some people wave their hands about more than others, so do some authors, often putting their italics into their characters’ mouths to avoid seeming too histrionic themselves. Jane Austen, brought up to discreet deportment and quiet speech, can be vicious with italics:

Nowadays writers are advised against adverbs. It would never do for Yazz, in Benardine Evaristo’s Girl, Woman, Other, to think something “sarcastically”, but Evaristo suggests sarcasm with italics: once she’s graduated and working, she’s going to sell her house, correction, their house, which is worth a small fortune thanks to Mum’s gentrification of Brixton By the way that’s not my missing full stop – Evaristo uses punctuation sparingly. But she relishes italics, as when Yazz’s Mum forbears to mention The Boyfriend, glimpsed when he dropped her off in his car. So much suspicion, pride, worry, judgement conveyed by italics and a couple of capital letters.

My italics for the title acknowledge someone else wrote Girl, Woman, Other (shame). Fortunately Evaristo isn’t referring to the film The Boyfriend or confusion might arise. At least I’m assuming she isn’t, I’ve only just started it. Could be a bookblogger trap…

Authors may choose italics to differentiate between a character’s inner thoughts or dreams and what they say aloud, and also to differentiate timelines or points of view, clarifying them for the reader. Unhelpfully, I can’t find examples on my shelves now. I hope one turns up before this blog post goes out. I do find whole pages and paragraphs of italics hard to read and wish authors with split timelines/narrators would find some other way round the problem. I definitely read one recently. Maybe I threw it out for that reason.

Italics may be used for a recurring phrase, reminding us of what’s at stake or a character’s obsession. Olive Kitteridge‘s visit to her son in New York is punctuated by the neighbour’s parrot repeating Praise the Lord. Italics differentiate a letter or document from the rest of the text, or economically summarise occasions when the same thing was repeated. These examples are from The Confessions of Frannie Langton, by Sara Collins, whose short prologue and epilogue are also italicised.

Agatha Christie’s Poirot, stereotypical histrionic foreigner, lives and breathes italics.

You’ll notice Poirot’s italicised French, like the Latin in the previous example. Italics of “foreign” words could mean three things: i) you do know what this means, dear readers ii) work it out from the context or iii) here’s something to look up, dunce. Here’s an extraordinarily basic example from Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray. “Society feels…the highest respectability is of much less importance than the possession of a good chef.”

Indie authors decide from themselves how much to italicise “foreign” words, preferably with professional editorial advice, and publishers have varying house styles. The trend is towards italicising less. Some authors reasonably object to “othering”. When words their characters use in daily discourse are italicised, it has the effect of making them suddenly shout “Look at this exotic word!” mid-flow. This article argues, with entertaining, informative examples, why such an approach simply won’t do in a world where all cultures and idioms deserve equal respect. I found it on Ask a Book Editor (Facebook) and reposted it on Writers for Diversity (Facebook too). On both sites it elicited a lively, helpful thread with much food for thought.

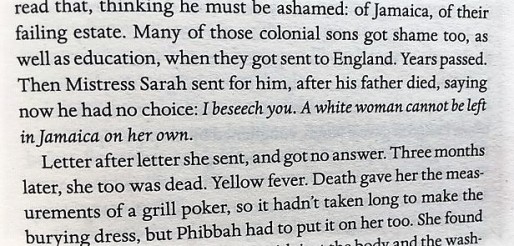

A rule of thumb is to explain meaning either directly or through context, unless you know the words have been incorporated into the language you’re writing in (check a good dictionary if unsure). Here’s The Song of Achilles, elegantly whisking the reader over the obstacle, and another example from The Braid by Laetitia Colombani, itself translated from French, which I think could have omitted the explanation as the context is clear:

![IMG_5878[7126]](https://jessicanorrie.files.wordpress.com/2020/07/img_58787126.jpg?w=453&h=244)

I’ve learnt something from writing this blog that’s probably obvious but needed spelling out for me. Too many italics over-egg the pudding. Like flouncy curtains or thick make-up, CAPITALS or exclamation marks!!! Flicking through my books I found the writers I most admire use hardly any. I’m not saying the examples above are bad, the books they come from are wonderful in their different ways or I wouldn’t include them. But less is definitely more. I suspect my Novel 3 has rather a lot. Inside I’m thinking: is that why it hasn’t been snapped up by a publisher yet?

©Jessica Norrie 2020

Reblogged this on Writing Despite Computers and Programmes and commented:

Now here is a very timely and well-reasoned post.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you! Oops, that was an exclamation mark and they’re not always appreciated either…

LikeLike

Well reasoned post.

Ever since I read a writer shouldn’t use italics or adverbs my use of them in writing has increased exponentially.

Has to be reblogged!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for reblogging. Rules are made to be broken – all we poor authors can do is try not to get caught!

LikeLike

Jessica, newcomer here courtesy of Roger’s link. I use italics and bold often in my posts. Usually, I use italics to highlight quoted material and bold to highlight titles of books, articles and movies. Sometimes, I will use both to highlight a theme quote – emphasizing if you read anything, read this.

I was also taught not to start paragraphs with “And” or “But,” yet I ignore that rule, too. All the best. Keith

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello Keith, nice to “meet” you. I’m not sure my post is about rules, or even guidelines. It’s more a summary of my observations. Subconsciously I was probably also aiming my comments mainly at the authors of novels (like myself) where bold would certainly be out of place and italics should I think be kept for special occasions. I think for bloggers and writers of non fiction the “rules” if any are a bit different. Bloggers especially seek and then want to keep attention for shorter pieces that are likely to be read on a phone or other small screen; therefore anything they can do to break up the text is a good idea (like Roger with his many images). But yes, rules are made to be broken. And often are. I’ll even end with a preposition, now I’ve worked out how to.

LikeLike

I use italics in three places: emphasis, foreign words likely to be unfamiliar to readers, and the point-of-view character’s unspoken thoughts. As you say, sparing is best.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for your comment. I guess the difficulty lies in knowing which words may be unfamiliar and that means knowing in advance who your readers are.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I must admit I don’t use that degree of precision. If a foreign word or phrase is encountered in English frequently enough (e.g., savoir faire, menage a trois, Schadenfreude, Zeitgeist) I don’t italicize. One clue is whether a word is picked up as a spelling error by Word or other spell checker. (Apologies for no diacritics.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

No need to worry about the diacritics – I’m not sure WordPress has caught up with them yet, for comments anyway. (If I want to use them I usually copy and paste from Word.) On your wider point, I think italics matter less when using standard European language terms like the ones you mention. It’s a question of personal taste and style, and for me less is more. But it does seem reasonable to me when people don’t want their languages /cultures viewed as minority, exotic or other and putting them in italics can have that effect. The article I quoted goes into it more fully and did open my eyes. Thanks for your thoughts – this post has raised a lot more interest than I expected!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for this very interesting information, Jessica. Most of this was very new to me, but i think its useful to know. Best wishes, Michael

LikeLiked by 1 person

hi Michael – I have no idea why your valued comment went to my spam box, some unilateral WordPress decision no doubt. Always good to hear. I’m sure italics use varies according to different languages so no wonder some new to you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dont worry Jessica! WP has its own rules. Thank you for responding, and enjoy your week. Michael

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s Word Puzzle at the moment, not Word Press!

LikeLiked by 1 person

😉

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Anita Dawes & Jaye Marie ~ Authors.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting post about the use of italics… I also liked the different use of coloured writing. I haven’t managed to learn how to do this yet, though!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi jenanita. It may depend on the WordPress theme you use, but what I do is to go to the capital A at the top of the menu when I’m drafting a post, click on the down arrow next to it, highlight the section i want to colour and choose a colour. Much the same as when you’re writing a Word document in fact. Hope that helps and thanks for your comment and the reblog.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m with the new editor now… and that is a whole new ball game!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m avoiding it until I have no choice!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I love all the different things I can do, but some are not easy to learn…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much Sally. I was surprised to get quite so much mileage out of this subject but it turned out there’s was a lot to say!

LikeLike

Well… that’s interesting. I don’t mind italics in books, but I can see the point that too much might not be a good idea.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I know – it seemed like such a dry subject and then when I started looking into it there was lots to say! (Imagine that “lots” in italics!)

LikeLiked by 2 people

Hehehe!

LikeLiked by 2 people

I tend to use sparingly in my fiction but use to differentiate reviews from other text when posting promotions with reviews. But on reflection seeing its use in the books I have read does help highlight foreign words or thoughts rather than speech very usefully.. I have pressed for Monday evening.. something to think about as always Jessica..x

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you Sally. My post is mainly about fiction but I think for a blog such as yours you have to find ways of differentiating the many sections of text and italics come in useful for that. We’ll see what your readers think on Monday!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am sure they will be as engaged as always Jessica…. enjoy your weekend.. x

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting. Agree sparing is best. Though some authors use exclamation marks more than others eg Belinda Bauer in Snap – a marvellous book IMO

LikeLiked by 2 people

I haven’t read that – will take a look. Watch out or a post on !!! sometimes after that perhaps! Thanks for comment.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I try to be sparing with italics, particuarly in dialog. After reading your post, I’m thinking it might not be a bad idea for me to consult a style guide every now and again.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I think as long as you keep being sparing in mind, that’s good enough. If you publish with a traditional house, they’ll sort it out. And the foreign words debate is an interesting one which has certainly changed recently. Thanks for commenting.

LikeLiked by 1 person